From The Horse-World of London by William John Gordon (1893)

. . . . Our cab horses are generally Irish, many of them being shipped from Waterford. They come over unshod, in order that they may do no damage, and to keep them quiet they have their lips tied down; and what with this lip-tying, and the sea passage, and the change of climate, it takes them about eight weeks to get into working order, during which they are gradually drilled into shape, first in double harness and then in single harness, round the squares and quiet thoroughfares.

As a rule, they are four years old when they arrive, they cost 30L, they last only three years, and they are then sold to go into the tradesman’s cart; but horses are rising in value, and cost more to buy and fetch more to sell than they used to do. This, of course, refers to the bulk of the horses, which, as in the omnibus service, are mostly mares. There are some that cost more, some that cost less; some that last longer, some that do not last as long; and on the cab-rank there is a fair sprinkling of British horses and a few foreigners, but the thoroughbreds of whom we have heard are as rare as the doctors, warriors, and members of the Athenaeum Club who are said to drive them.

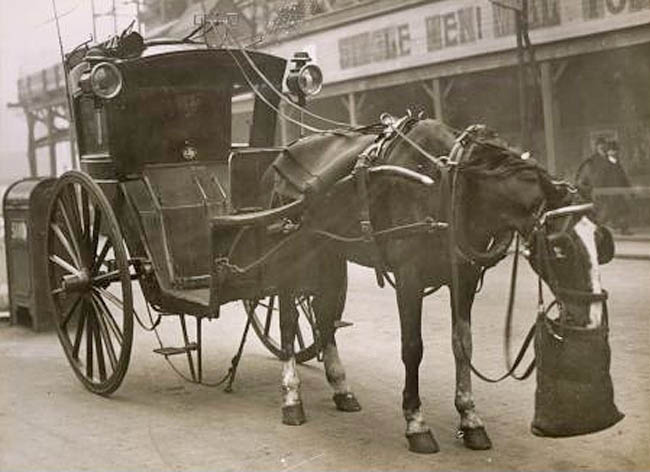

A cab horse is well fed; hansom horses average a sack of corn each a week; and they want it, for in the six days during the season they are driven over two hundred miles. There is nothing out of the way in a day’s work of forty miles; and this with a weight of half a ton behind, including the cab and driver, but not the passengers. The way in which the horse is worked varies in different yards and with different men. There are over 3,500 cab-owners in London, and as some of them own a hundred and more cabs, there must be a large number who have but one or two cabs, and perhaps two or three horses, when the horses have a hard time of it. Many are worked on the ‘one horse power’ principle, in which the cab, generally a four-wheeler, goes out at eight in the morning and comes back at eight at night. The fourwheelers that frequent the railway stations have two horses, the first going out at seven in the morning and returning about two in the afternoon, the second going out to stay at the station till ten, and then perhaps loitering about the theatres with a view to picking up a last fare.

When a horse is bought by the cab-master it is occasionally numbered, but oftener named from some trivial circumstance connected with its purchase, or from some event chronicled in the morning newspapers. A whole chapter might be written on the names of the London cab horses, which are assuredly more curious than elegant. Three horses we know of bought on a hot day were Scorch, Blaze, and Blister; three others bought on a dirty morning were Mud, Slush, and Puddle; two brought home in a snowstorm were named Sleet and Blizzard; four that came in the rain were Oilskin, Sou’-wester, Gaiters, and Umbrella. Even the time of day has furnished a name, and Ten o’clock, Eight-sharp, and Nine-fifteen have been met with . . . Some horses are named from the peculiarities of the dealer or his man, and in one stable there were at one time Curseman, Sandyman, Collars, Necktie, Checkshirt, and Scarfpin. The political element is, of course, manifest, and in almost every stable there are Roseberies and Randies, Salisburies and Gladstones, Smiths and Dizzies. Some stables are all Derby winners, some all dramas, some all songs, some all towns. It is the exception for a horse to be named after any peculiarity of its own, unless it be an objectionable one; and it would never do to give it a Christian name, with or without a qualifying adjective, which might lead to its being mistaken for one of the men in the yard.

The favourite colour for a cab horse is brown; the one least sought after is grey. A grey horse will not do in a hansom, unless for railway work where the cabs are taken in rotation and the quality or colour of the horse is of no consequence. Why clubland should object to grey horses is not known, but the fact remains that a man with a grey horse will get fewer fares with him than with a brown one. One explanation is that the light hairs float off and show on dark clothes, but this is hardly satisfying, and it seems safer to put the matter down to fashion. Anyhow, a hansom cabman will not take out a grey horse if he can help it, unless it be an exceptionally ‘gassy’ one, gassy being ‘cabbish’ for showy. But not so a four-wheeler man; if he can have a grey horse he will, the reason being that if ever a housemaid goes for a cab she will, if she has a choice, pick out the grey horse. At least, so says the trade, which may, of course, be prejudiced or romancing; but the prejudice or the romance is known all over London.

London has 600 cabstands, exclusive of those in the City and on private ground, such as the railway stations. A few of these are always full; a few have never had a cab on them even though they may have existed for years. The 600 cabstands on an average afford accommodation for eleven vehicles each. The rest of the cabs are either carrying passengers or else plying empty along such streets as Piccadilly, where they are a nuisance to all but those who want cabs. The same thing may, however, be said of the cabstands, and, considering the convenience that ‘ crawlers’ afford, it is only the very strenuous reformer who would abolish them entirely, if it were possible to do so.

Out of the 15,000 cabmen, about 2,000 are convicted every year for drunkenness, cruelty, wilfull misbehaviour, loitering, plying, obstruction, stopping on the wrong side of the road, delaying, leaving their cabs unattended, etc, etc. The cabman who ‘knows his business best’ is the one who can crawl judiciously without getting into trouble with the police, resulting for a first offence in the famous ‘two-and-six and two,’ which means half-a crown fine and a florin costs.

At many of the stands there is a ‘shelter,’ which is much larger inside than a glance at the exterior would lead one to suppose. The shelters are generally farmed from the Shelter Fund Society by some old cabman. They are the cabman’s restaurants, and the cabman, as a rule, is not so much a large drinker as a large eater. At One shelter lately the great feature was boiled rabbit and pickled pork at two o’clock in the morning, and for weeks a small warren of Ostenders was consumed nightly.

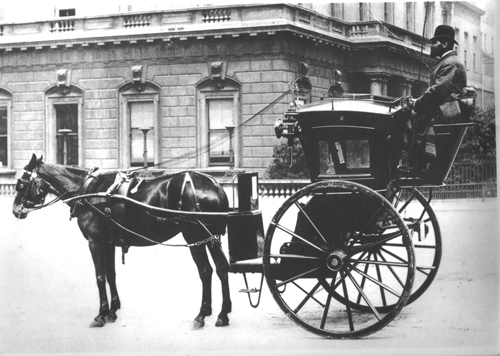

The two-wheeler improves every year. There are many hansoms now in London as good in every way as private carriages, and these will often have a fifty guinea horse in their shafts. The four-wheeler improves but microscopically, and, though it becomes no worse than it used to be, it touches a depth which is by no means desirable. Most cabs are varnished twice a year, some are varnished but once, and that, of course, is just before inspection day, when the new annual licence is applied for. On that morning many a newly varnished mockery will journey gingerly to Clerkenwell, and just satisfy the inspector’s lenient eye, returning triumphantly with the inside and outside plates and the stencilled certificate on its back, which show that the vehicle has passed muster, and that the owner has paid 21. for a licence to work it in the London streets. Besides the 21., the owner has to pay fifteen shillings carriage duty to Somerset House; and, for a licence and the badge to drive, the cabman has to pay to the police five shillings.

The cabman has to pass an examination as well as the vehicle, but the vehicle is examined every year, while the cabman is only examined once, and then not in personal appearance, though there may be a bias that way, but in an elementary knowledge of London topography. The knowledge required is not very great, and 1,500 candidates apply in a year, but it is interesting to note that out of every 100 candidates 34 are ‘ploughed’—a much higher percentage of rejections than exists among the vehicles.

The cabman takes his licence to the owner whom he desires to make his ‘master.’ He takes the cab out on trust, leaving his licence as a deposit so long as he remains in the same employment. The engagement is terminable at any time, and when the man changes masters his old master has to fill in on the back of his licence the length of time he has been in his service. At the end of the year the man takes the endorsed licence accounting for his year’s work to New Scotland Yard, and there gets a clean one covering another twelve months.

The amount paid by the man for the day’s hire varies with the vehicle, the master, and the season. It is much less really than it is nominally, owing to the numerous occasions on which allowances are made for bad luck and bad weather. Continuous wet is not cabmen’s weather; what they like is a showery day, or, what is better, a fine morning and a wet afternoon, or a series of scorching hot days when people find the other means of conveyance too stuffy for comfort. Although the amount is frequently stated to be more, the average for hansoms during the last year over several yards was nine shillings for the first three months in the year, then a rise every week of a shilling a day to the end of May, when it remained at the maximum of eighteen shillings till the second week in June, when it dropped a shilling a week down to the nine shillings at which it will remain for the rest of the year. The height of the London cab season is thus from the Derby week to the Ascot week, the one day being the Thursday after the Derby. If you wish to go to the Derby in a hansom you pay 31., of which 11. is extra profit, it being estimated that the man would have taken 21. if he remained in London. And, curiously enough, the distance to and from Epsom is the average day’s journey of a London cab horse.

Very very good article! thank you!