In this series, we turn to the words of Mr. Charles Dickens which appeared in the March 30, 1850 edition of the publication he edited, Household Words. The following article is chock full of details about how the Post Office operated in Victorian London and also about the mail and other items it processed on a daily basis.

The piece follows the progress of two gentlemen who make a visit to the Post Office –

|

| Great National Post-Office in St. Martin’s-le-Grand |

Most people are aware that the Great National Post-office in St. Martin’s-le-Grand is divided into halves by a passage, whose sides are perforated with what is called the ” Window Department.” Here huge slits gape for letters, whole sashes yawn for newspapers, or wooden panes open for clerks to frame their large faces, like giant visages in the slides of a Magic Lantern; and to answer inquiries, or receive unstamped paid letters. The southern side is devoted to the London District Post, and the northern to what still continues to be called the “Inland Department,” although foreign, colonial, and other outlandish correspondence now passes through it. It was with the London District Branch that the two gentlemen first appeared to have business.

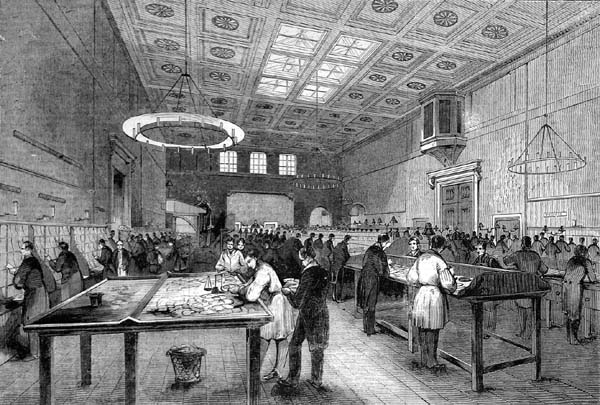

Having been led through a maze of offices and passages more or less dark, they found themselves—like knights-errant in a fairy tale—” in an enormous hall, illumined by myriads of lights.” Without being exactly transformed into statues, or stricken fast asleep, the occupants of this hall (whose name was Legion) appeared to be in an enchanted state of idleness. Among a wilderness of long tables, and of desks not unlike those on which buttermen perform their active parts of legerdemain in making ” pats”—only these desks were covered with black cloth—they were reading books, talking together, wandering about, lying down, or drinking coffee—apparently quite unused to doing any work, and not at all expectant of ever having anything to do, but die.

In a few minutes, and without any preparation, a great stir began at one end of this hall, and a long train of private performers, in the highest state of excitement, poured in, getting up, on an immense scale, the first scene in the ” Miller and his Men.” Each had a sack on his back; each bent under its weight; and the bare sight of these sacks, as if by magic, changed all the readers, all the talkers, all the wanderers, all the liers-down, all the coffee-drinkers, into a colony of human ants.

For the sacks were great sheepskin bags of letters tumbling in from the receiving-houses. Anon they looked like whole flocks suddenly struck all of a heap, ready for slaughter; for a ruthless individual stood at a table, with sleeves tucked up and knife in hand, who rapidly cut their throats, dived into their insides, abstracted their contents, and finally skinned them. “For every letter we leave behind,” said the bagopener, in answer to an inquiry, ” we are fined half-a-crown. That’s why we turn them inside out.”

The mysterious visitors closely scrutinised the letters that were disgorged. These were from all parts of London to all parts of London and to the provinces and to the far-off quarters of the globe. An acute postman might guess the broad tenor of their contents by their covers:—business letters are in big envelopes, official letters in long ones, and lawyers’ letters in none at all; the tinted and lace-bordered mean Valentines, the black-bordered tell of grief, and the radiant with white enamel announce marriage. When the despatch of the Fleet-street receiving-house appeared the visitors tracked it, and the operations of the clerk who separated the three bundles of which it consisted were closely followed. With the prying curiosity which now only began to show itself, one of the intruders took a copy of the bill which accompanied the letters. It set forth in three lines that there were so many ” Stamped,” so many ” Prepaid,” and so many ” Unpaid.”

The clerk counted the stamped letters like lightning, and a flash of red gleaming past showed the inquirers that one of their epistles was safe. Suddenly the motion was stopped; the official had instinctively detected that one letter was insufficiently adorned with the Queen’s profile, and he weighed and taxed it double in a twinkling. Having proved the number of stamped letters to be exactly as per account rendered, he went on checking off the prepaid, turning up the sender’s green missive in the process. He then dealt with the unpaid, amongst which the lookers-on perceived their yellow one. The cash column was computed and cast in a single thought, and a short-hand mark, signifying ” quite correct,” dismissed the Fleet-street bill upon a file, for the leisurely scrutiny of the Receiver-General’s office. All the other letters, and all the other bills of all the other receiving-houses, were going through the same routine at all the other tables; and these performances are repeated ten times in every day, all the year round, Sundays excepted.

” You perceived,” said one of the two friends, “that in the rapid process of counting our stamped letter gleamed past like a meteor, whilst our money-paid and unpaid epistles remained long enough under observation for a careful reading of the superscriptions.”

“That delay,” said an intelligent official, “is occasioned because the latter are unstamped. Such letters cause a great complication of trouble, wholly avoided by the use of Queen’s heads. Every officer through whose hands they pass—from the receiving-house-keeper to the carriers who deliver them at their destinations—has to give and take a cash account of each. If the public would put stamps on all letters, it would save us, and therefore itself, some thousands a year.”

” What are the proportions of the stamped to the prepaid and unpaid letters which pass through all the post-offices during the year?”

” We can tell within a very near approximation to correctness: 337,500,000 passed through the post-offices of the United Kingdom during last year, and to every 100 of them about 50 had stamps; 46 were prepaid with pennies; and only 4 were committed to the box unpaid.”

While one of the visitors was receiving this information, the other had followed his variegated letters to the next process; which was that of stamping on the sealed face, in red ink, the date and hour of despatch. The letters are ranged in a long row, like a pack of cards thrown across a table, and so fast does the stamper’s hand move, that he can mark 6000 in an hour. While defacing the Queen’s heads on the other side, he counts as he thumps, till he enumerates fifty, when he dodges his stamp on one side to put his black mark on a piece of plain paper. All these memoranda are afterwards collected by the president, who reckoning fifty letters to every black mark, gets a near approximation to the number that have passed through the office.