It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a Regency era lady with a penchant for making and collecting music must have a designated room for doing so.

If one studies the floor plans of most stately homes as they appear today, one will find a room designated the music room, even if said room only houses a single instrument. This became common practice in the late nineteenth century, but most of these rooms were once used as parlors or drawing rooms. They were not designed specifically as music rooms.

As strange as it seems, with the emphasis on musical accomplishment expected of young ladies beginning in the eighteenth-century and becoming nearly a mania during the Regency era, before the middle of the eighteenth-century the inclusion of a specifically designed and designated music room in house plans for both stately homes and town mansions was rare. Beginning in the 1760’s, the inclusion of this room in plans for new homes and renovations for existing homes became increasingly more common. This indicates a major shift in the role of music in the domestic and social lives of the residents of these homes.

Perhaps one of the first set of house plans which recorded a specific room dedicated to music was drawn by no less a designer than Robert Adam himself. In 1760, as lead architect for the creation of Sir Nathaniel Curzon’s showplace – Kedleston Hall – Adam drew plans for a neoclassical Temple of Art which encompassed an enfilade on one entire side of the entrance hall. It consisted of a music room, a drawing room, and a library. These rooms were so labelled in a catalogue printed in 1769, which was used to guide tourists around the house. This catalogue was reprinted at least four times by 1800 and would have been well-known to any wealthy landowner and / or peer looking to build or renovate a home.

|

||||

| The Music Room at Kedleston Hall |

An impetus of Adam’s design of this arrangement of rooms was the ability to make available a large audience chamber by opening the three rooms into each other by a series of folding doors. (If you look at the right hand edge of the photo above you will see the door frame leading into the next room.) This arrangement enabled the entire area to be used in featuring a talented family musician or even a professional for a large gathering of people. One must remember Kedleston Hall was primarily a place to house the Curzon family’s extensive collections of art and to entertain on a grand scale. Music, especially that provided by the talented daughters of a household, began to play a great part in these entertainments. (It wasn’t the Miss America Pageant, but it came close. And was so much more refined than auctioning one’s daughter off at Tattersall’s.)

Adam was exceedingly interested in music and went on to design music rooms and even keyboard instrument cases for both town and country homes for a wide range of clients.

Stop by this blog squarepianos.com/blog.html to see two posts on the piano and harpsichord cases he designed for Catherine the Great. Yes, that Catherine the Great.

This business of designing a music room which could be closed off for private tutoring and practice and then opened up to other rooms by way of a series of folding doors carried over into Adam’s designs for houses in London as well. Whilst in Town the impetus was partly due to the availability of professional singers and musicians to hire in addition to those entertainments provided by wealthy amateurs; more often it was to show off the musical accomplishments of the women in the household – the male patrons’ wives or daughters. It also provided a place to house the instruments and music collections of these ladies. There can be no doubt the ladies of the house had a great deal to say about the addition of music rooms to the plans for their homes both in the country and in Town.

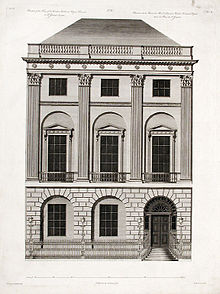

Adam expanded this practice in the design of the townhouse of Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn at Number 20 St. James Square in 1774. In addition to being the sion of the wealthiest family in Wales (a position this family maintained for 200 years,) Sir Watkin was a great patron of the arts, particularly music. He sponsored so many musical events in his London home he was even the subject of a caricature depicting himself and members of the nobility attending one of the Concerts of Ancient Music, a long running series of concerts he sponsored in London.

The design for Sir Watkin’s townhouse provided a formal dining room on the first floor which opened by way of two-leaf doors leading into the music room. In addition to an exquisite ceiling and music-themed plaster work throughout the music room, Adam also designed the case for the organ gifted to by Sir Watkin to his first wife.

|

||||

| Robert Adam’s design for the front facade of No. 20 St. James Square. |

|

||

| Robert Adam’s design for the Music Room ceiling at No.20 St. James Square |

|

||

| Music Room Highclere Castle. Notice the double doors to the left. |

|

|||||

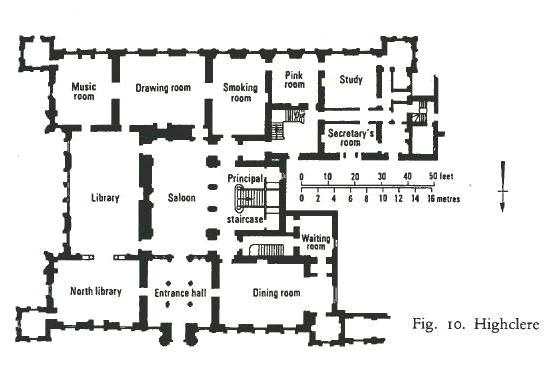

| Floor plan of Highclere Castle. Notice the position of the music room as anchor to the drawing room and library. |