Me, poor man, my library

was dukedom large enough.

The Tempest

William Shakespeare

I cannot comprehend the neglect of a family library in such days as these.

Fitzwilliam Darcy

Pride and Prejudice

When I have a house of my own, I shall be miserable if I have not an excellent library.

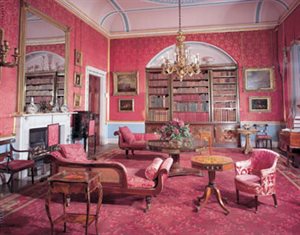

One can hardly envision an English stately home without a library somewhere about the premises. Think of all the murder mysteries without a place to discover an inconvenient corpse if this were not true. Or what about all of those Regency romance heroes and heroines searching for a respite from the tedium of a ball, only to discover the one lurking about in their host’s barely lit book room? One shudders to think!

It is surprising to discover large private libraries were rare in England before the 18th century. Before then, they were more likely to be found in the hands of kings, great lords, monasteries, and universities. However, a number of occurrences related to the Reformation of the 16th century – the spread of book printing, country houses began to take the place of monasteries and castles, the libraries of said monasteries were dispersed in sales as the monasteries were closed, and universities in the throes of humanist zeal purged their libraries, also in sales, all of which led to the acquisition of books by aristocrats eager to build their own book collections. Some of these aristocrats were genuine scholars and book lovers eager to preserve England’s and the world’s intellectual heritage. Others simply wanted to keep up with the neighbors. In three or four hundred years, very little has changed. Never underestimate the power of the male ego to turn Mine’s bigger than yours. into a competition.

The fashionable bar for libraries in country houses was set in the 18th century by Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford. His elegant library at Wimpole Hall, designed by James Gibbs in 1730, consisted of a huge room built to house his collection of over 50,000 books and 350,000 pamphlets and three small cabinet chambers leading into the library which housed his collection of coins, seals, antique cameos, and manuscripts. Unfortunately, his debts forced the sale of the entire collection on his death in 1741. Or perhaps his heir simply wasn’t the bookish type and opted to get rid of the library rather than land or other assets. Whatever the reasons for the dispersal of the library, the Earl of Oxford fired the starting shot across the bow of every aristocrat in England. The race was on to amass the largest and most unique and valuable collection of books and to erect the most spectacular temple to the written word in which to house them.

|

| Far end library – Wimpole Hall |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I will be covering a great deal more about the advent of libraries in stately homes in my follow-up post. (Yes, there will be a follow-up post. There is a reason I write novels and not short stories.) The library in an English country house was made up of a beautifully constructed room designed for the specific purpose of housing books. Once the room was designed, crafted, and finished it was filled, of course, with books. However, there was another, little studied, aspect of creating those beautiful libraries which I would like to address in brief in this post. After all, if you are going to dispose of a body it is helpful to have a few things in the room behind which to hide it. A dead body is so much more effective if it is found suddenly and results in screaming servants or fainting ladies. And remember those heroes and heroines meeting in the library? What happens if there is nothing on which, against which, or behind which to tryst? I’m all for romance, but carpet burns, even on a very expensive Aubusson carpet, do tend to ruin the mood.

Thus begs the question, what sort of furnishings might one find in his lordship’s library? What started out as an ostentatious room to display one’s intellectual snobbery soon became a refuge for the man of the house. His lordship could invariably be found “hiding” in his library when any number of unpleasant events occurred, including, but not limited to – his wife. Over the years it eventually morphed into a sort of living area for the family. This may be responsible for the sheer size of such rooms. Family togetherness was all well and good, but lets not becom

e too bourgeoisie about this. By the late Regency it would not be unusual to find his lordship at his desk, her ladyship reading before the fire, the daughters at the piano at the far end of the library, and the sons perusing maps on a library table or sneaking a peek at grandfather’s naughty books shelved on the top shelves at the far end of the library.

Here are a few items one might have found in the stately home library to facilitate the room’s many purposes.

Library Steps –

Most libraries included shelves going nearly to the ceiling. Every inch of space was utilized. If a mezzanine balcony was not added to access those shelves at the higher levels, library steps were used to peruse the shelves above one’s head. The set below includes a post with which to steady oneself when descending with an armload of books.

|

| 19th Century Mahogany Library Steps |

|

|

| A sturdier version, also mahogany 19th century. |

|

|

Once one had retrieved the books one wished to read, a comfortable chair in which to read them was necessary. Of course, most libraries included one or more fireplaces for heat and chairs and sofas were often arranged around them for reading and conversation. These items – chairs, sofas, and even chaises for those inclined to recline and read – might come from other areas of the house. (Trysting on a chaise is far more comfortable than trysting on a library table or worse. Remember the carpet burn?) More often, chairs ordered specifically for the library were put into use. Here are some examples of chairs designed for use in the library.

|

| 19th Century English Leather Library Chair |

|

|

This looks to be a very comfortable chair and has the added advantage of wheels should one wish to move it closer to the fire or away from noisy family and guests. The chair above is in fantastic condition considering it is over 200 years old. Craftsmanship, ladies and gentlemen. Craftsmanship.

|

| 19th Century Leather Library Chairs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

These two were undoubtedly used on either side of a library fireplace. The sides might shield one from the prying eyes of others, or in the case of two people sitting before they fire they might shield a private conversation from others in the library.

|

| English Regency Library Chair

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<

td style="text-align: center;">

|

|

|

|

|

I find this particular chair fascinating. The shelf on the back can be made to lay flat or can be dropped to the back of the chair completely. One can only assume it was made for someone to kneel in the chair and read over the back or perhaps the shelf was for the reader to stack extra books. No matter its function it is a uniquely designed chair and in all design books and catalogues it is listed strictly as a library chair.

|

| 19th Century Rosewood Library Chair |

This chair represents the evolution towards comfort and relaxation in Regency era furniture, an evolution which started in those items designed for both the library and the bedchamber. A clear indication, perhaps, of these rooms being viewed as those where one might be more at ease than in the more public and formally social rooms of the house.

Bookcases –

Of course, the walls of libraries were lined with built-in shelves, inset bookcases or free standing bookcases pressed to the walls. In addition to these large shelving units for books, a library might contain other places in which or on which to house books. There were smaller bookcases, library tables, and even movable cases on which to organize one’s books for further use.

This lovely piece is a Regency era mahogany bookshelf with castors on the bottom to enable it to be moved easily about the library. The drawers were for manuscripts or folios. I would imagine a butler or footman might have found it useful in returning books to the shelves after his lordship left them scattered about the library.

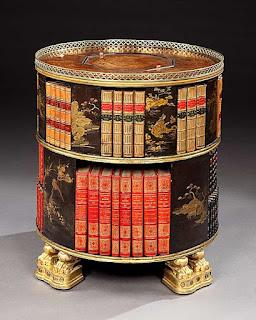

The above is a Regency era parcel gilt lacquer circular bookcase, and, yes, it spins. In the photograph, it is used to hold sets of books. One might imagine it next to a comfy chair with a few days’ or weeks’ worth of books on it within reach of his lordship or her ladyship during a long winter’s reading season.

Library Tables –

Library tables were present in any 18th and 19th century library. They were used for a variety of purposes. They were designed to be placed in the middle of a room as surfaces to spread out maps, folios, or a selection of books. It is important to remember whilst these were family libraries, they were also resources for local vicars, magistrates, scholars, and anyone from the estate and local villages who might want to make use of them with his lordship’s permission. They were often used to look over design plans for houses, gardens and estates. These rooms were not simply for show. Most, if not all, were used every day for every sort of pursuit today’s public libraries might encounter.

Library Globes –

A final item to complete the furnishing of the stately home library might be a globe. They were used to plot a journey, check the location of an investment property, or perhaps to plan a young man’s Grand Tour. There were terrestrial globes and also globes of the constellations for those with an astronomical bent.

|

| Pair of 21 inch Regency Globes – Terrestrial and Constellations for those with Navy affiliations. |

|

| Rare Regency Era 36 inch terrestrial globe by Cary’s of London |

There you have it, a few of the odds and ends, unique pieces designed and created for use in the magnificent libraries of those exquisite country houses. They created and continue to create an atmosphere of elegance and intellectual pursuit. They gave these spaces a personal touch, often an indication of the family’s character, attitudes, and even their relationships with each other. These pieces are also markers in the evolution of the views of houses as homes rather than simply showplaces. Items previously designed with an eye to their ability to stress the owner’s wealth, success, and power began to morph into pieces crafted to be practical, to blend in with their surroundings, and to promote concepts of ease and relaxation. Books became escapes as well as instruments of learning. Reading became a pastime enjoyed by all, rather than a strictly scholarly pursuit. As much as we owe the owners of these libraries for the preservation of our literary heritage, we also owe them thanks for making reading more than simply a search for knowledge, but also an endless source of joy.