Victoria here, peeking into another great country house, this one the home of the Cecil family, the Marquesses of Salisbury, Hatfield House.

When I took the course on English Country Houses at Worcester College, Oxford University, our don, Geoffrey Tyack, took us to a number of historically significant houses, beginning with medieval manors and carrying into the Tudor houses, the most lavish of which are known as Prodigy Houses. These were the estates acquired by the “new” men who served the crown because of their intelligence, education, and ability rather than by familial ties and nepotism. Once these “new” men got into positions of power, however, they did all they could to advance the interests of their families, particularly at court. One part of this quest was to have a large, profitable and magnificent estate at which to entertain, impress, and achieve strategic partnerships, whether by friendship, marriage or intrigue. These houses, naturally, had to be large and luxurious enough to accommodate both royalty and its entourage.

One of the most important of the men who served Elizabeth I was William Cecil, Lord Burghley (1520-1598), who was Lord High Treasurer. He built Burghley House (above) between 1555 and 1587 in a more-than-grand scale. His eldest son, 1st Earl of Exeter, carried on the family at Burghley.

Robert Cecil (1563-1612), a younger son of Lord Burghley, made his own way in the world and did a bang-up job of it, becoming a chief minister to Elizabeth I and Lord Treasurer to her successor, James I. As Professor Tyack has written, Robert Cecil “also inherited his father’s taste for magnificent building.”

Robert Cecil (1563-1612), a younger son of Lord Burghley, made his own way in the world and did a bang-up job of it, becoming a chief minister to Elizabeth I and Lord Treasurer to her successor, James I. As Professor Tyack has written, Robert Cecil “also inherited his father’s taste for magnificent building.”

Robert Cecil was made the 1st Earl of Salisbury and took over, by exchange with the King for another house called Theobalds, the estate at Hatfield. The Old Palace there, above and right, had been the childhood home of Elizabeth I. The building you see in the pictures was only part of the huge complex, most of which the Earl demolished. The Old Palace now serves as a tourist attraction and a venue for meetings, conferences, banquets and weddings.

Lord Salisbury created for himself the foremost example of Jacobean architecture in Britain. Carpenter and Surveyor (the profession of architect was barely in its infancy) Robert Lyminge laid out the house to the earl’s preferences, incorporating familiar Tudor features (e.g. the capped cupolas at the corners and the oriel windows), and newer styles such as the classical loggia on the south front.

Entering the Marble Hall, I could see that the 1st Earl had indeed achieved his goal of creating a gathering place of incomparable and extravagant richness. It could not fail to impress friends or enemies, retainers or royalty. The ceiling is original though enhanced in the Victorian era with more colorful paintings. Tapestries from Brussels cover the walls, illustrating stories from mythology. This room has always been used for entertaining whether banquets, balls or masques.

Left is the rainbow portrait of Elizabeth I, which contains the motto Non sine sole iris, translated as “no rainbow without the sun.” The anonymous painter was heavily into flattery, one imagines. The portrait hangs in the Marble Hall, where no visitor could mistake its significance.

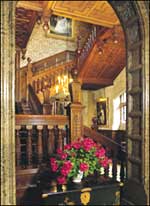

The Grand Staircase is a fine example of Jacobean wood-carving expertise. Finished in 1611, it includes gates at the bottom step to keep the dogs from lounging around in the state rooms upstairs. One of the figures carved into a newel post is John Tradescant (c.1570-1638), the great plant collector on behalf of Robert Cecil and his new garden. Tradescant brought back from his world travels many fruit trees, vines, seeds and bulbs, greatly expanding the scope of English gardening, all of which enhanced his employer’s prestige.

On the first floor (what we in the U.S. would call the second floor), the magnificent State rooms are divided into two apartments, one each for the king and queen. In King James’s Drawing Room a life size statue of the king stands above the fireplace. The walls are hung with old master paintings.

Long galleries were required in all Jacobean houses but few are as splendid as this one, with its fine cabinetry holding treasured gemstones and its gilded ceiling. Two gigantic fireplaces heated the gallery, where one could enjoy a morning stroll without combating the elements.

Many more rooms are open to the public, including a chapel with fine old stained glass, some of it more than 400 years old.

The house is much the same today as it was when first built, though one wing was destroyed by fire in 1835, taking the life of the first Marchioness of Salisbury, nee Emily Mary Hill, then age 85. The dowager, as she was known, was writing by candlelight, it was said, and her hair caught fire, eventually engulfing the entire west wing of the house. Emily (1750-1835), wife of the first Marquess, portrayed here by Sir Joshua Reynolds about 1780, was a famed Tory political hostess and sportswoman.

Her son, James, the 2nd Marquess, married Frances Mary (1802-1839), known as the Gascoyne Heiress, and changed the family name to Gascoyne-Cecil. The story of Frances, often known as Fanny, is told in the book The Gascoyne Heiress: the Life and Diaries of Frances Mary Gascoyne-Cecil by Carola Oman, published in1968 by Hodder & Stoughton in London. These diaries are full of exciting political news, for Fanny became a close confidante of the Duke of Wellington, who had long been a family friend. Hatfield House is home to much Wellington memorabilia; both with her husband and children or solo, Fanny often visited Wellington, listened to his every word and recorded most of them for posterity.

This black and white reproduction of Fanny’s portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence does not do justice to her charm.

Like many country houses, Hatfield is also a business enterprise. Many events takes place here and no doubt you have caught a glimpse of the house or garden in one of the doszens of movies which shot scenes on the premises, such as Shakespeare in Love (1998), The Importance of Being Earnest (2002), or The Golden Age (2006).

The current dowager marchioness is well-known as a gardener, though she claims to be entirely an amateur. Not only did she redo entirely the gardens at Hatfield, she also has designed gardens for many others, including the Prince of Wales at Highgrove. She has been associated with a number of books on gardening, though she no longer lives at Hatfield.

I took so many pictures in the Hatfield Garden that I could almost do a book myself. But have you ever come home and realized that your pictures completely failed to capture the essence of the subject matter? Below is a shot of a rose against the brick of the Old Palace followed by some lovely wisteria blossoms. Somehow it was all so much more beautiful on site!

Finally, an aerial view of Hatfield House.

The Holker estate belongs to Lord and Lady Cavendish, a branch of the family of the present 12th Duke of Devonshire. It has been in the Cavendish-Devonshire family for many years, coming into their possession by marriage. Largely rebuilt in red sandstone after a fire in 1871, its style is neo-Elizabethan. one of the popular recreated architectural fashions of the Victorian Era.

The Holker estate belongs to Lord and Lady Cavendish, a branch of the family of the present 12th Duke of Devonshire. It has been in the Cavendish-Devonshire family for many years, coming into their possession by marriage. Largely rebuilt in red sandstone after a fire in 1871, its style is neo-Elizabethan. one of the popular recreated architectural fashions of the Victorian Era.

In the Blue Guide to Country Houses of England, Geoffrey Tyack writes of Holker Hall, “Few houses open to the public convey better than Holker the sense of late-Victorian aristocratic life and tastes.”

In the Blue Guide to Country Houses of England, Geoffrey Tyack writes of Holker Hall, “Few houses open to the public convey better than Holker the sense of late-Victorian aristocratic life and tastes.”  The estate is a busy commercial concern, including forestry, lumbering, and slate cutting businesses as well as agricultural produce, tourism, hunting and fishing, and many special events such as festivals, concerts, and exhibitions. The fallow deer herds are maintained for their traditional beauty as well as for their meat.

The estate is a busy commercial concern, including forestry, lumbering, and slate cutting businesses as well as agricultural produce, tourism, hunting and fishing, and many special events such as festivals, concerts, and exhibitions. The fallow deer herds are maintained for their traditional beauty as well as for their meat.  By the way, in the September-October 2010 issue of Victoria magazine, there are also excellent articles on the Lake District and its benefactress, the late author Beatrix Potter, who created Peter Rabbit and all his friends.

By the way, in the September-October 2010 issue of Victoria magazine, there are also excellent articles on the Lake District and its benefactress, the late author Beatrix Potter, who created Peter Rabbit and all his friends.