From The Letter-bag of Lady Elizabeth Spencer-Stanhope

“Your father is very well. He was sorry for the fate of the Slave Trade Bill last night. The Elopement and distress in the House of Petre has been the chief subject of conversation for the last few days. Miss Petre made her escape from her father’s house in Norfolk with her Brothers’ tutor on Monday last. It is said they are at Worcester and married only by a Catholic Priest. However, Lord and Lady P. are gone there and it is expected she will be brought back to-night. They can do nothing but get her married to the man at Church. She is 18, he 30, and no Gentleman. She was advertised and 20 guineas reward offered to anyone who could give an account of the stray sheep. It is a sad History. What misery this idle girl has caused her parents, and probably ensured her own for life.

Marianne Stanhope to John Spencer Stanhope.

The Miss Petre referred to above was Maria Juliana, daughter of Robert Edward, 9th Baron Petre. She was born 22 January 1787, married on 30th April 1805, to Stephen Philips, Esq., and died 27th January 1824. I have been unable to find much else concerning her life, but here is her obituary, as it appeared in The Catholic Spectator: “The Hon. Mrs. Philips, wife of Stephen Philips, Esq. of H. M. Customs, and eldest daughter of the late Rt. Hon. Edw. Lord Petre, and Lady Mary, surviving, of a decline, aged 37. To the ardent and unremitting zeal of this Lady, in her personal and most charitable attentions to the Female Catholic Charity School, at Stratford, Essex, may principally be attributed her lamented and premature decease. She has left five children and a husband to deplore the loss of a model for the Christian wife and mother.”

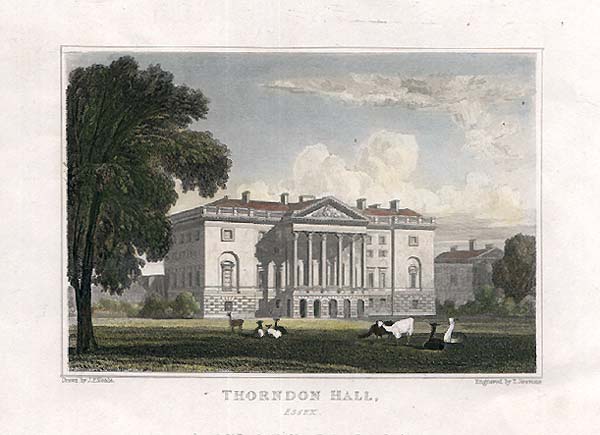

However shocking his daughter’s elopement may have been for Lord Petre, there was more disappointment ahead. Like many other aristocrats before and after, Lord Petre’s home, Thornton Hall, was chosen as a base for a royal visit in October of 1778 by King George III and Queen Charlotte. And, like others, Lord Petre went to great expense to prepare for his royal guests. We have the following account of the preparations and the visit from Reminiscences For My Children by Catharine Mary Howard (1838) –

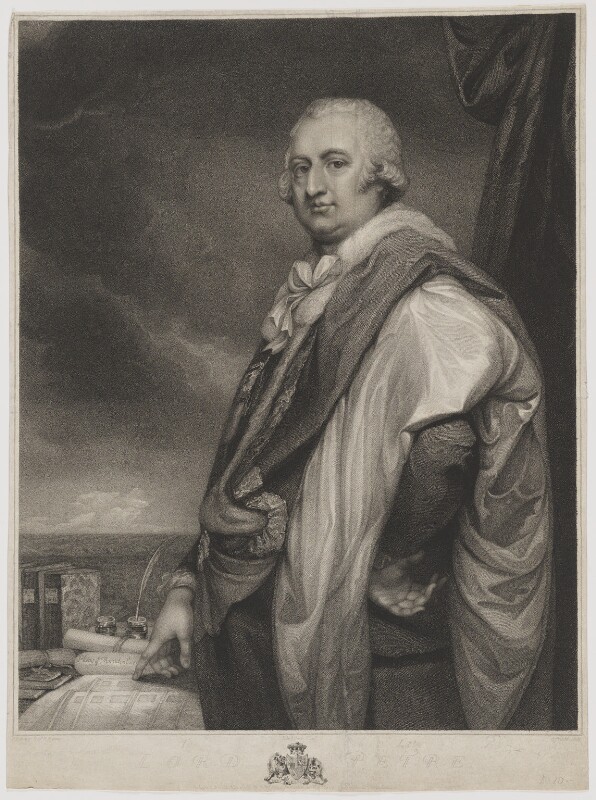

|

| General Lord Amherst |

September 22nd—General Lord Amherst was commanded by his Majesty to inform Lord Petre, that he was graciously pleased to accept of his offer to make Thorndon his residence, during his intended review of the troops encamped on Warley Common, on or about the 5th of October. Lord Petre, anxious to receive his sovereign with every mark of respect, duty, and affection, becoming an attached and loyal subject, set about immediately making every necessary preparation for his entertainment, which the vicinity of Thorndon to the capital enabled him to do with more expedition. His lordship sent for Mr. Bracken, his upholsterer, and asked him whether it was possible, in so short a time, to re-furnish the drawing-rooms, the state bed-room, and dressing-rooms —the drawing-room being forty feet by twenty-five, and twenty-three feet high, which is the height of all the rooms on the first floor. He replied, it might be done if a sufficient quantity of damask, of English manufacture, (as was ordered,) could be procured to cover those spacious apartments. Among other things ordered, were fifty tabourets to be covered with damask, as only kings and queens upon such occasions sit upon chairs. In a few hours he sent down patterns, of which a beautiful light green was chosen for the drawing-rooms and the King’s dressing-room, and a red and white damask for the state bed-room and the Queen’s dressing-room.

“Mr. Davy, the house-steward, was despatched the next day to town, to procure trades-people of every description, who arrived at Thorndon in various conveyances, both public and private, amounting to one hundred, and who were all lodged and fed in the house. He was also daily employed in providing every luxury for the King’s table; and was empowered by Lord Petre to order a service of gold, in addition to the family plate, which was very considerable. Much, also, was hired, and a quantity borrowed from the Duke of Norfolk, assisted by some families in the neighbourhood— Lord Waldegrave, Lady Mildemay, and Mr. Conyers. Every thing went on briskly, but no decided day had been named for the King’s arrival.

“October 3rd—An express came from Lord Amherst, to announce that his Majesty would not be at Thorndon before the 19th instant. The cooks and confectioners were therefore sent back to London; and three large dinners were given to the neighbours, to which the officers and their ladies were invited, who partook of the good things that had already been prepared, while the workpeople went on more leisurely, and with less fatigue.

“On the 15th, the fourteen additional men-cooks and confectioners returned, and re-commenced their culinary labours with great spirit, so that all was in readiness, in every department, by the 18th October.

“October 19th, three o’clock Behold! in the avenue, the finest sight of the kind that ever was seen !—The sun bright—troops drawn up on each side—innumerable people—the King and Queen appearing with their numerous equipages, horse guards, attendants, etc. and numberless horsemen sent by Lord Petre to meet them, headed by his land-steward, with all the people he could collect— the park of artillery saluting, which was re-echoed in the woods with the shouts of the people—the rapidity with which the King’s chaise ran on, scarcely five minutes having elapsed, from the time of its appearance at the top of the rising avenue, (a full mile and a half from the house,) to their Majesties coming up to the door—the lawn in one instant covered with horsemen—and the horses panting—all contributed to resemble the work of enchantment! From Brentwood, a double row of carriages had placed themselves behind the troops, the horses being taken off to prevent accidents.

“Lord and Lady Petre received their Royal Visitors at the door. Lord Petre handed the Queen up stairs, while the King, with Lady Petre, walked on together through the entrance-hall— carpeted for the occasion up to the carriage-door— towards the first drawing-room, into the great drawing-room, which shall henceforth be designated by the presence-chamber, where two state chairs were placed on a raised platform. Lord and Lady Petre then kissed their Majesties’ hands, who soon shook off all form by their easy manner. They asked directly to see the house, and, followed by their suite, went through all the different apartments. On their return to the presence-chamber, the King desired to see Miss Petre, whom he played with, and afterwards took a great deal of notice of.

“At four o’clock, dinner was announced, when Lord Petre handed the Queen to the dining-room. Her chair alone was placed at the table, but her Majesty desired the ladies to sit down; and tabourets were immediately brought forward for Lady Egremont, lady of the bed-chamber, Lady Amherst, and Lady Petre. On no other occasion excepting at commerce, were they asked to sit down.

“His Majesty dined in the great hall, a couvert being laid only for him. He also desired the gentlemen to sit down; and stools were immediately placed near the table for Lord Lothian, gold stick, Lord Carmarthen, chamberlain to the Queen, General Carpenter, equerry to the King, Colonel Harcourt and Colonel St. John, aides-decamp, Lord Amherst, General Pearson, Majorgeneral Sir David Lindsay, as commanding officer of the day, Major-general Morrison, and Majorgeneral Fawcett. Lord Petre sat on the left hand of the King, and acted as cup-bearer. After the first glass was drunk, his Majesty ordered the wine round to his right, that he might not take the trouble to get up again.

“. . . . . In rising from table at eight o’clock, Lord Petre poured rose-water upon his Majesty’s hands, from a golden ewer and basin which were given by Mary, Queen of Scots, to the Earl of Derwentwater, his maternal grandfather. He then conducted his Majesty to the presence-chamber, bearing lights before him.

“After coffee, the King conversed for half an hour with the gentlemen in the outer drawingroom, to whom he talked of the army, and, with Lord Petre, chiefly about the camp. All the company then took their departure, leaving only the attendants.

“The King immediately proposed playing at commerce, and made the following party:—Lady Egremont, Lady Amherst, Lady Petre, Lord Lothian, Lord Carmarthen, Colonel St. John, and Colonel Harcourt. The latter won the first pool, and Lord Petre the second.

“Supper was prepared in the great hall at twelve o’clock. The Queen only sat down to supper, around whose chair the King, with the gentlemen, and a great number of attendants, stood at the bottom of the table. At one o’clock, their Majesties retired. Lord Petre carried lights before the King, and Lady Petre before the Queen, to their apartments.

“Here a little occurrence caused some disappointment. As their Majesties always carried their own little beds with them, the state bed had to be removed to make place for them, from within the gilt-iron guard that surrounded it. Fortunately, the tester was fastened from above, with the curtains, independent of the bedstead, and remained to form a stately awning to the two ordinary red and white check tent-beds.

“The next morning their Majesties breakfasted alone in the presence-chamber. Between nine and ten o’clock, they sent for Lord and Lady Petre, with whom they walked about the house, and up and down the south portico of the great saloon, until the carriages were ready to convey them to Warley Common. Here Lord Petre had prepared a stand, tacked and furnished in a very sumptuous manner, which was placed in the most advantageous position for seeing the sham-fight and the military movements, with which the King expressed his approbation in the strongest terms, but which were reported in the Gazette in an ordinary style.

“All passed on in the same manner as on the preceding day, excepting that the peers, and colonels of the regiments encamped at Warley, were asked to dine at the King’s table, making a party of thirty. One hundred and thirty dishes were served up, besides high ornamental decorations in the centre. Among the dainties gathered from all parts of England, I observed in the poulterer’s bill, a bustard, marked five guineas.

“His Majesty was in high spirits, conversed with cheerfulness and freedom, and did not rise from table till ten o’clock ; after which he proposed another pool at commerce, which his Majesty won, and in the course of the game drew kings twice. The second time he threw them on the table, he said, `Here are these things again, here are these things again.’

“At twelve, their Majesties retired to rest; and next morning they breakfasted in the presencechamber, as they had done on the preceding day. At ten o’clock, Lord and Lady Petre, with their little daughter, were sent for by the King, who throwing open one of the windows, that the whole party might be seen by the populace, who had collected from all parts in great crowds in front of the house, remained a considerable time—the King holding Miss Petre before him, and Lord Petre standing on his right, with Lady Petre on the left of the Queen. Their Majesties then, in the most obliging manner, expressed their thanks for the kind and handsome reception they had met with at Thorndon, which they condescendingly repeated several times.

“Lord and Lady Petre had the honour to kiss their Majesties’ hands, as they had done on their arrival. Lord Petre then handed the King and Queen into their carriage—drawn by six beautiful greys—who drove off for Navestock, to dine with Lord and Lady Waldegrave, where Lord and Lady Petre were commanded to meet their Majesties; and they went up to town the following day, to attend the drawing-room at St. James’s.

“As vails were not then abolished, the King left a hundred guineas for the servants, as also money for the poor.”

And so he might in return for such lavish entertainments. The People’s History of Essex by Duffield William Coller (1861) provides further details into the entertainments organized for the King: “The street and roadway from the London entrance of the town, down to the park gate, a distance of nearly two miles, were lined with soldiery; and the royal pair passed beneath a triumphal arch to the hull door, where they were received by Lord and Lady Petre. A royal levee, a grand dinner party, a concert, and a display of fireworks, filled the roll of festivity at the baronial hall; while the loyalty of Brentwood blazed forth at night in a general illumination, as brilliant as it could be made at a time when gas as yet lay slumbering undiscovered in its heap of coal dust. The following day his Majesty reviewed the little army which lay encamped at Warley, and afterwards held a levee upon the ground for the reception of the military officers and county gentry. While this was passing upon the green turf of the common—while the cannon were thundering out in mimic fight, troops of horse flying across the plain, and columns of infantry crashing through the neighbouring woods to show royalty how a battle was lost and won—a fairy-like surprise was preparing at Thorndon Hall. At the west end of the magnificent dining-room, a noble orchestra rose as if by magic. On the front was emblazoned the royal arms, with Fame sounding her trumpet, and underneath, in large characters, were the words —” Vivant Bex et Regina.” On each side were finely-executed portraits of their Majesties, and guardian angels crowning them with laurel. The orchestra itself was filled with artists of firstrate talent The whole was carefully concealed till the royal party and the other guests were seated, and the course had been served, when on the first flourish of the royal fork, the screen was suddenly removed. The fine strains of ” God save the King” bursting out from the midst of this flash of light and these things of beauty, gave it the air of an enchanted scene; and general expressions of delight greeted the noble host.”

We now return to Reminiscences For My Children for the sorry aftermath of the Royal visit and to learn what Lord Petre, who had spent so much, on so many levels, received for his pains.

“From that period no particular mark of attention in any manner was ever shown to Lord and Lady Petre, by their Majesties King George III. and Queen Charlotte. On the contrary, they were not even asked to the Queen’s concerts or private parties the following winter, or to any other entertainment ever after, solely on the plea of their religion (they were Catholics); and in 1798, his Majesty refused to sign Lord Petre’s son’s commission to a volunteer corps he had raised, because, his Majesty said, he could not help being aware that he was a Roman Catholic, having been in the chapel at Thorndon House.”

It seems odd that the King should claim to only have discovered that Lord Petre was a Catholic after his visit, as Lord Petre had been a force in the move for Catholic Emancipation, all neatly laid out in this entry from Wikipedia.

As a side note, the Thorndon Hall website relates the following: “At the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 Lord William Petre (11th Baron 1793 to 1850) is said to have captured Marengo, the grey Arabian horse of Napoleon I of France, although in talking with his decendent the current Lord Petre he does not believe that his ancestor would have been at the battle being a Catholic. However whether or not the Baron was present at the battlefield it is believed that he acquired the horse and brought it back to the Thorndon Hall, later selling it to Lieutenant-Colonel Angerstein of the Grenadier Guards for stud. Marengo lived on for another 11 years and died at the age of 38. The horse’s skeleton was preserved and is now on display at the National Army Museum in Chelsea, London.”