By Guest Blogger Regina Scott

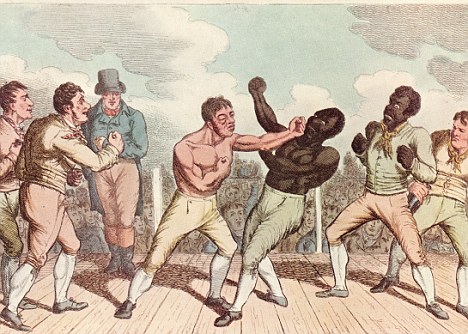

Perhaps two smacks on the chin? Certainly any sporting-mad fellow in Regency England would agree. Boxing was one of the most popular sports in late eighteenth century/early nineteenth century England. It was so popular, as many as 20,000 people flocked to each match, resulting in a few fisticuffs outside the ring, raucous behavior, heavy drinking, and massive wagering of up to 200,000 pounds. Thieves sought to fix fights. Pickpockets roamed the crowds looking for easy meat. Small wonder fights were outlawed in London proper during the Regency.

That didn’t stop the Fancy, those avid followers of pugilism. Boxing was considered thoroughly British. The French didn’t box. The Americans merely copied. Who wouldn’t support such a manly sport? The Prince Regent and his brothers the Duke of York and the Duke of Clarence were all in. When His Royal Highness was coronated, he enlisted the aid of a group of boxers to protect the streets around his route.

Major newspapers like the Morning Post and the Times covered the sport, and at least half a dozen sporting newspapers and magazines devoted sections to it. Pierce Egan, the sports writer who first called boxing the sweet science, was widely followed, and Boxiania, the collection of his writings on the subject, ran to six volumes. Even Lord Byron took lessons from Gentleman Jackson, perhaps the most famous of the Regency-era boxers, from his boxing salon at Number 13 Bond Street.

But boxing wasn’t just for the rich and influential. Any man might attend a boxing match. The privileged rubbed elbows with clerks and millworkers. The more common folk also joined with the upper classes to discuss boxing and watch demonstrations of pugilism at the Daffy Club, run by former boxing champion Jem Belcher from his Castle Tavern, Holborn, beginning in 1814.

Until 1814, private patrons had put up prizes for the fights, a practice that easily led to abuses. That year, Gentleman Jackson helped sponsor the Pugilistic Club with about 120 subscribers who contributed a certain amount annually to pay for prizes. Jackson was also instrumental in setting up Fives Court in Little St. Martin’s Street as an exhibition hall for fighting. Matches there were generally benefits to raise money for fighters down on their luck.

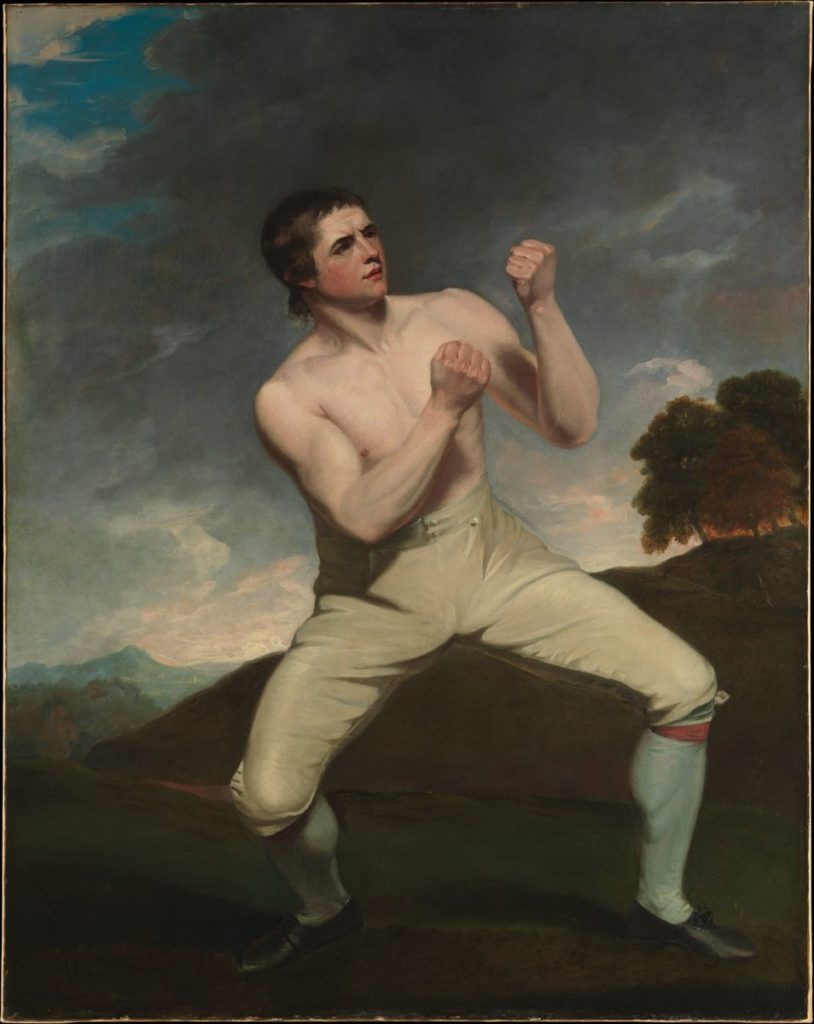

And boxers were too easily down on their luck. The sport was brutal. Hair pulling and eye gouging were allowed, and deaths in the boxing ring were not unknown. Still, boxers entered the boxing square with a swagger and nicknames like The Nailer, Big Ben (50 years before there was a Big Ben), and the Light Tapper (I gather this was irony). Well-known American fighters, William Richmond and Tom Molineaux, both African-Americans, also came to London to fight and drew large crowds. The reigning champion from 1809 to 1822, Tom Cribb, was always a favorite.

What exactly did it look like to fight with bare knuckles back in the day? Stay tuned to the next installment for all the details!

Regina Scott is the award-winning author of more than 40 works of sweet historical romance, several of which feature Regency gentlemen who box. In Never Kneel to a Knight, a boxer being knighted for saving the prince’s life must prove to a Society lady who is miles out of his league that their love is meant to be.

You’ll find more on Regina online at her website, on her blog, or on Facebook.