King William IV by James Lonsdale, 1830

Today we begin a series of posts that will give some insight into the personalities and home life of King William IV and Queen Adelaide, a royal pair whom, in my personal opinion, have not been enough by the history books. To illustrate just a small slice of their lives at Windsor, we offer excerpts from a book entitled, Letters the Late Miss Clitherow of Boston House, Middlesex, With A Brief Account of Boston House and the Clitherow Family, edited by Rev. G. Cecil White. As the Reverend himself states in his preface: “The following pages are mainly compiled from certain letters by Miss Mary Clitherow, which have come into the editor’s possession. They afford glimpses of the Court at that time, with reference not so much to public functions as to their Majesties’ more private relations with persons honoured with their friendship.”

Colonel and Mrs. Clitherow lived at Boston House in Brentford along with the Colonel's sister Mary, the author of the following letters, who was two years his senior. About the year 1824 they became acquainted with the Duke of Clarence, afterwards King William IV., who then resided at Bushey, of which park he was Ranger; and they were admitted to an unusual degree of intimacy with their Royal neighbours, observing in their intercourse with them an honesty not usually found in courtiers, but quite in keeping with the family motto, 'Loyal, yet true.' So close did this intimacy become that, after his accession, the King nicknamed Miss Clitherow 'Princess Augusta,' in allusion to her being the old maid of the family as the Princess was in his own, and when inquiring for her of Colonel or Mrs. Clitherow would say, 'How is your Princess Augusta?' It may of interest to note that in the library of Boston House were hung many portraits of the Clitherow family by leading artists of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Among these should be specially noted a pastile by Zoffany of Mr. and Mrs.and Miss Child, taken in the porch at Osterley. Mrs. Child (nee Jodrell) was the sister of Mrs. Clitherow, and afterwards married (1791) the third Lord Ducie. Miss Child married the tenth Earl of Westmoreland, and became the mother of the Countess of Jersey.

|

| Boston House, Brentford |

Although, however, the Clitherows were frequent guests at Windsor and St. James's, they were not courtiers in the common acceptation of that term. They sought neither place nor preferment, and received no signal mark of Royal favour. Miss Clitherow never even attended a Drawing Room, and the Colonel and his wife only appear to have done so on one occasion, when the Queen remarked: 'I knew Miss Clitherow would not come; it is too public. She had almost left off going out till we made her come to St. James's.' Miss Clitherow was naturally of a quiet and retiring disposition, while her own account of her introduction to the Court, and of the independent spirit which pervaded the family, is interesting not only in itself but as illustrating the kindly sincerity of the King and Queen. Writing to an old friend in November, 1830, Miss Clitherow says: 'I can hardly believe that I feel as much at home in the Royal presence as in any other first society, but it is the fact. It is seven years that my brother and Mr. [sic] Clitherow have been noticed, but I am only just come out now. For many years my health did not allow of my dining out, and I got so out of the habit that I avoided it, and quite escaped being asked to Bushey till the Duke became King. Before George IV. was buried they were invited; no party but the Royal brothers and sisters and the Fitz-Clarences. They did me the honour to talk of me, the King calling me my brother's Princess Augusta, in allusion to my being the old maid of the family, and then added: "I can't see why she does not some out; you must dine here Tuesday, and bring her." So the deed was done. Refuse I could not. I dined at Bushey, then twice at St. James's, then on the Queen's birthday at Bushey, and then went to Windsor Castle on Friday and stayed till after church on Sunday, and now to dinner at St. James's last Monday. So that actually [in less than five months] the little old maid of Boston House has dined seven times with King William IV., and honestly I have liked it. There is a kindness and ease in their manner towards us that must be gratifying . . . and when we come home what a feeling of comfort we have in not being obliged to live in that circle, with all the insincerity so often belonging to courtiers! I am very sure my dear Jane's honest manner and the sound judgment which she ventures to express to Her Majesty makes her such a favourite. Much as we are noticed, we do not court them, and never have asked the slightest favour. When they first went to Windsor our friends said: "You must drive over and put your names down." "No," Mrs. Clitherow said, "we were asked to the Queen's birthday; I will not go before the King's, it will look like pushing to be asked." And we received our invitation to Windsor before we had called. When we came away, the King expressed a hope to see us at Brighton, as he knew we frequently went into Sussex. Our friends all were for sending us thither, but it did not suit us. Don't you like independence? As soon as they came to town we did put our names down. Miss Fitz-Clarence writes herself to Mrs. Clitherow to inform her of her intended marriage with Lord Falkland, and Mrs. Henry is employed to write and invite us to dinner to meet our own friends. So

I think we rather go the right way to please them.'

|

| Queen Adelaide |

The following extract is from a letter dated November 20, 1830 -

'We had dined there (St. James's Palace), and it seems almost like vain boasting, but it was a party made for us. When the King told Mrs. Henry to write and invite us, he said: "I shall only ask Colonel Clitherow's friends that I have met at Boston House." And it was the Duke of Dorset,[*] Lord[**] and Lady Mayo, the Archbishop and Mrs. Howley, the rest of the company his own family, the Duke of Sussex,[***] and a few of the Household-in-waiting. There could not be a greater compliment. The Queen shows a decided partiality for Mrs. Clitherow. In the evening she sat down to a French table, and called to her to sit by her. The King came in and sat down on the other side of Mrs. Clitherow. She rose to retire, but he said: "Sit down, ma'am--sit down." Two boxes were placed before him, and he said to Miss Fitz-Clarence[****]: "Amelia, I want pen and ink." Away she went, and brought a beautiful gold inkstand, and he signed his name, I am sure, a hundred times, passed the papers to Mrs. Clitherow, and she to the Queen, who put them on the blotting-paper, then folded them neatly and put them in their little case to enable them to pack into the boxes again, conversation going on all the time. When the business was over, the King took my brother to a sofa, and chatted a long time, inquiring into the state of things in our neighbourhood, policemen, etc. The Queen's new band was playing beautifully all the evening, which she said she had ordered to have my brother's opinion. The late King's private band cost the King L18,000 a year. It was dismissed, and a small band is formed--I believe I may say all English, and many of the juvenile performers whom she patronizes. Her dress was particularly elegant, white, and all English manufacture. She made us observe her blend was as handsome as Lady Mayo's French blend. "I hope all the ladies will patronize the English blend of silk," she said. She is a very pretty figure, and her dress so moderate, sleeves and head-dress much less than the hideous fashion.'

[*] Charles Sackville Germain, fifth Duke of Dorset, K.G., was a son of the first Viscount Sackville, and born 1767. He became Viscount Sackville 1785, and succeeded his cousin, the fourth Duke of Dorset, in 1815.

[**] John Bourke, fourth Earl of Mayo, born 1766, succeeded his father 1794.

[***] H.R.H. was the sixth son of H.M. George III., born 1773, and was unmarried.

[****] The King's youngest daughter, by Mrs. Jordan; born 1807, married, 1830, the ninth Viscount Falkland.

The following letter bears testimony to the King's conscientious discharge of duty and to royal life at Windsor Castle.

'April 13, 1831.

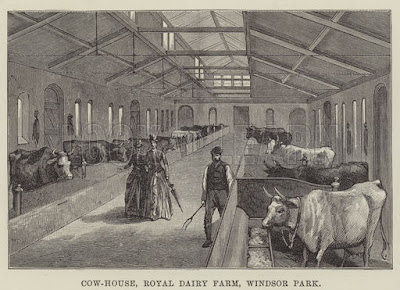

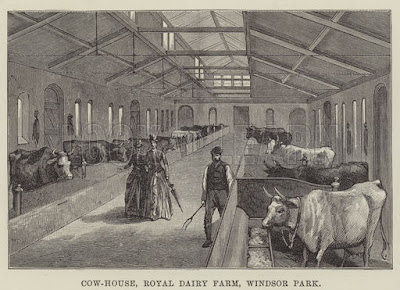

. . . . . . 'On a Sunday they only have a carriage or two for those who cannot walk. She (Queen Adelaide) never has her riding party, and often goes to the evening service; but she dedicated the time to us to show us her walks, flower-garden, a cottage that is building for her, her beautiful dairy, with a little neat country body like our Betty at the farm, and her labourers' cottages, whence out came the children running to her. One had a kind word, another a pat on the head.

|

| Copyright Look and Learn |

'Then we saw the farmyard, pigs, cows, etc. Then she took us all over Frogmore Garden, which is extensive and very pretty, and then back by dairy and slopes. We were absolutely three hours, walking a good pace. We numbered about fourteen, but, with the usual thought, two carriages were at Frogmore to convey home the tired ones. Only two gave in. The day was very lovely, and her animation and spirits quite delightful. And this is our Queen--not an atom of pride or finery, yet dignified in the highest degree when necessary to be Majesty. God grant her peace and comfort may not be broke in upon!

|

| Queen Adelaide by Sir David Wilkie |

. . . . . 'Their Majesties are not seen till three o'clock. They breakfast and lunch in their private apartments. Then she comes out and arranges the morning excursions--all sorts of carriages and saddle-horses. She is a beautiful horse-woman, and rides about three hours, a good, merry pace. She sets forth with Maids of Honour and Ladies attendant, and generally returns surrounded by the gentlemen only, for it is understood she dispenses with their attendance the moment they get fatigued, and so they sneak off one by one. There are plenty of grooms to attend.

'Mrs. Clitherow got a quiet ride with my brother and the Duke of Dorset, whom the Queen always asks to m

eet us, as she always met him here in former times. Jane returned for the gentlemen to attend the Queen, and Jane and I went a long drive about the park with the Princess Augusta, who was most chatty and good-humoured.

'On Sunday between church and luncheon we were summoned to the Queen's own apartment to present to her a picture of Bushey House. We have a young friend who has made a very pretty picture of old Boston House, and the happy thought of getting Bushey struck my brother. The Queen is so fond of Bushey! She looked some time at it, then turned to Jane and said, "I shall value it. You know how I love dear Bushey; but I value more the kind thought of having it painted for me." Jane told her when she became Queen her happiest days were past, and she often reminds her of it. She perpetually asks her questions, and says, "You are so honest; you tell me true." She draws extremely well. She took a likeness one evening of one of her beauties, Miss Bagot, and when she was showing her portfolio everyone exclaimed it was so very like.

'Poor Mrs. Kennedy Erskine[*] was there. She lived in her own apartments. Mrs. Fox,[**] her sister, and Miss Wilson took it by turns to dine with her. She was only married four years, was doatingly fond of her husband, and is left with three children.[***] The King went every evening when he came from the dinner-room and sat half an hour with her. On his return to the drawing-room the Queen had taken her work and Jane Clitherow into the music-room, while I remained at her table with the Princess Augusta. The King came up. "Ah, my two Princesses Augusta, this is very comfortable; now to business.' She had the official boxes, pen and ink all ready. He unlocked a box and set to work signing, the Princess rubbing them on the blotting-book and returning them into their cases. He signed seventy. Three times he was obliged to stop and put his hand in hot water, he had the cramp so severe in his fingers. When he signed the last he exclaimed, "Thank God, 'tis done!" He looked at me and said: "My dear madame, when I began signing I had 48,000 signatures my poor brother should have signed. I did them all, but I made a determination never to lay my head on my pillow till I had signed everything I ought on the day, cost me what it might. It is cruel suffering, but, thank God! 'tis only cramp; my health never was better." The Queen was all attention, came and stood by him, but neither she nor the Princess said anything. When he is in pain he likes perfect quiet and to be left alone.

'On Monday morning all left the Castle, and the great square full of carriages being packed was most amusing. The Queen stood at the Window with us. There were three fours of the King's, and nineteen pair of post-horses, besides the out-riders, guard of honour, etc., etc.

'My paper makes me end, or I could go on till to-morrow. Adieu, my good friend! If I have amused you for a few minutes I am well repaid.

'My best remembrances to your trio.

'Yours truly, 'M. C.'

[*] The King's fourth daughter, Augusta, born 1803, married, first, 1827, Hon. John Kennedy Erskine--he died 1831; secondly, 1836, Lord Frederick Gordon.

[**] The King's second daughter, Mary; born 1798, married, 1824, Colonel C. R. Fox, A.D.C. to the Queen.

[***] As her four children are subsequently mentioned, it may be noted that a posthumous child was born two or three months after this letter was written.

PART TWO COMING SOON!