A few years ago in Sebastopol in the Crimea I walked around a compelling recreation of a moment in the siege of the city during the Crimean war where the closest figures are almost life-size. This kind of model is called a diorama. In Windsor Museum we have our own diorama of a siege but ours in on a small scale, as are the others which pinpoint moments in the town’s history. They’re like miniature theatres, in glass-fronted cases and lit from above, all of them lively and dramatic, where you almost expects the tiny figures to continue the actions they’ve just begun.

|

| Part of a diorama showing the barons attacking Windsor Castle in 1216 © Windsor Museum |

The Windsor dioramas were commissioned in the 1950s from two friends, Judith Ackland and Mary Stella Edwards. They had met when at Regent Street Polytechnic in 1919, where they studied art, and afterwards they set up a home and studio together in a cottage called The Cabin, on the beautiful North Devon coast.

|

| The Cabin at Bucks Mills appledorearts.org |

For many years they spent the summers travelling, painting landscapes and selling their art, but after the Second World War, perhaps feeling they were too old for gipsy living, they started a new career making dioramas. After meticulous research into their subjects Mary painted the backgrounds, while Judith made the figures. She developed her own way of modelling figures which she called ‘Jackanda,’ using wire and compressed cotton-wool. Remarkably she could not only position her figures in a life-like way, but even on a miniature scale – each figure measures around 10 cms – she could create expression and in the case of historical characters recognisable portraits.

|

| Judith Ackland at work by Mary Stella Edwards Bucksmillscabin.blogspot.com |

The Windsor commissions came about after one of their dioramas was shown in the Guildhall as part of a Florence Nightingale centenary exhibition. The enlightened local council then asked the women to create a diorama for 1957, which would mark 350 years since John Norden’s map of Windsor in 1607.

Detail of John Norden’s 1607 map of Windsor

It was the first map of the town and shows the recently-built Market Hall (1596), with the old parish church behind. You can also see the pillory where wrong-doers were punished by being forced to stand pinioned by their neck and wrists, enduring cat-calls and, if unlucky, well-aimed fruit and vegetables (our Museum has a model pillory for visitors to stick their heads in, and a basket of fruit and veg., luckily fluffy, for friends and relations to throw).

Windsor Market-place in 1607 © Windsor Museum

The women peopled their market scene with imagination: a pig has made a bid for freedom, overturning a stall. Vegetables cascade across the ground and a plucked chicken lies with its feet in the air. There are other stalls, a group of women churning butter and behind them a butcher’s shop. An elderly man in a fur-edged robe, oblivious to the mayhem, must be someone important, perhaps the Mayor. A well-dressed woman with her page pulls her skirts out of the way.

Every detail has been researched, even to the type of coach seen in the background. One of the clever aspects of these dioramas is the way three-dimensional modelling merges with two-dimensional figures and landscape without any sharp division.

So successful was this scene that the women were asked to make another, and the following year they produced Windsor Bridge in the year 1770, again carefully researched.

Windsor Bridge in 1770

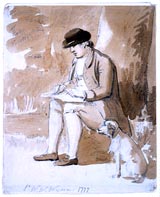

It’s a windy day, washing is blowing on a line and the women crossing the bridge have to hang on to their hats. An artist sitting at the corner

sketching is recognisably Paul Sandby, who painted many Windsor scenes including the bridge.

sketching is recognisably Paul Sandby, who painted many Windsor scenes including the bridge.

Paul Sandby sketching by Watkins William Winn

museumwales.ac.uk

The river is imagined running across the front of the diorama, and a boy is fishing in it. Masts of the barges which carried goods up and down the river can be seen, and bargees with their horses which hauled the boats along. Above looms the Castle, as it was in 1770, when the Round Tower was short and squat.

A year on and the women produced their most ambitious work: the Golden Jubilee celebrations of George III in Bachelors’ Acre in 1809, 150 years after the event.

On 25 October, when George III entered the 50th year of his reign, rejoicing was nationwide. In Windsor the so-called Bachelors of Windsor organised an ox-roast on the Acre – the name of this piece of open ground is thought to come from a time when butts were set up there for young men to practice their archery. Unfortunately the King, in his 71st year, lame, deaf and of poor sight, was too infirm to attend, but at one o’clock Queen Charlotte arrived on the arm of her second son, Frederick Duke of York, with most of her other children in tow (the Prince of Wales was also absent as he shunned public appearances because of his unpopularity over his treatment of his wife Caroline of Brunswick). The Mayor is in his robes, with the Corporation all dressed in blue with white wands of office. Even the cook had been given a blue smock and white silk stockings.

All the figures were researched from portraits in the Royal Collection. Princess Augusta is on the left in yellow, plump Princess Elizabeth is in blue, with the Duke of Kent, Queen Victoria’s father behind her, Princess Sophia is in pink with the really bad sheep of the family, the swaggering Ernest Duke of Cumberland at her side in uniform (he was believed to harbour incestuous thoughts about his sister Sophia and less than a year later suspected of killing his valet.) The Duke of Sussex is behind him. The royal party graciously partook of slices of the meat served on silver dishes, before retiring to the garden at the back for a ‘cold collation.’

Unfortunately because of its complexity and the illness of one of the women, the Jubilee diorama was late in delivery and over-budget. So for the next one, the Council laid down strict rules, and consequently it is the least detailed.

It shows the siege of Windsor Castle in 1216. After King John had failed to keep to the terms of Magna Carta (1215), the furious barons invited Prince Louis of France to take the English throne. Much of southern England fell into their hands, but Windsor Castle held out and after three months the attackers withdrew (they should have waited as King John died not long afterwards).

Once more, the Castle, the armour and weapons of war were meticulously researched. (It’s a pity you can’t see the horses behind the tents in the photo.) This is the diorama on show at the new Museum at the moment and the other three will take their turns. There are dressing-up clothes of the period for children, and one little boy was proud to have spotted the man who is collapsing with an arrow fired from the Castle walls in his neck.

Note the men lighting a bonfire against the Castle walls to weaken them.

Judith and Mary made other dioramas for Windsor, though they are simpler in scope, including one not in a case and with only three figures, which celebrates the Bayeux Tapestry.

Judith Ackland died in Devon in 1971. Thereafter Mary Stella Edwards organised exhibitions of her friend’s work and moved to what had been her family home in Staines, not far from Windsor, where she died in 1989. (The Cabin was kept as it was, and is now part-owned by the National Trust.) It had been a remarkable partnership and one we are proud to display in our Museum.

Mary Stella Edwards by Judith Ackland

Mary Stella Edwards and Judith Ackland

This is fascinating…another trip to Windsor to see them is on my horizon..Thanks, Hester.

Hester, these are marvelous! What talented women. If I do get to England in the next three weeks, I will definitely pay a visit to your lovely new museum.